Click here for a special Shabbat Chanukah prayer that honors the struggle of Soviet Jewry

SERMON #1

We Were As Dreamers: Soviet Jewry Advocacy in Perspective

Sermon by Rabbi Norman Patz

Caldwell, New Jersey

Think back twenty-five years. Soviet Jews were still trapped – prisoners of an oppressive and unpredictable totalitarian regime. Since the mid-1960s, increasing numbers of Soviet Jews had stood up and demanded permission to emigrate to freedom. Some thousands were allowed to leave in the 70s, but in the early1980s, the gates were shut.

American Jews had begun to raise their voices in protest after the Six Day War in 1967. We were challenged by Elie Wiesel, who called

us, not Soviet Jews, the “Jews of silence.” If Soviet Jews could speak out, in so doing risking their limited freedom and sometimes even their very lives, where were we? We needed to raise our voices to support them.

And, increasingly, we did. An advocacy movement for Soviet Jewry was formed. We made freedom for Soviet Jews a human rights issue. We adopted “prisoners of conscience” and wore bracelets carrying their names. We “twinned” with

refuseniks at b’nei mitzvah and Confirmation ceremonies. We sent delegations to the USSR to visit refusenik families, provide them with desperately needed supplies and, most of all, to let them know that they were not alone. We telephoned “our” families regularly, certain that the KGB was listening in. And we prayed.

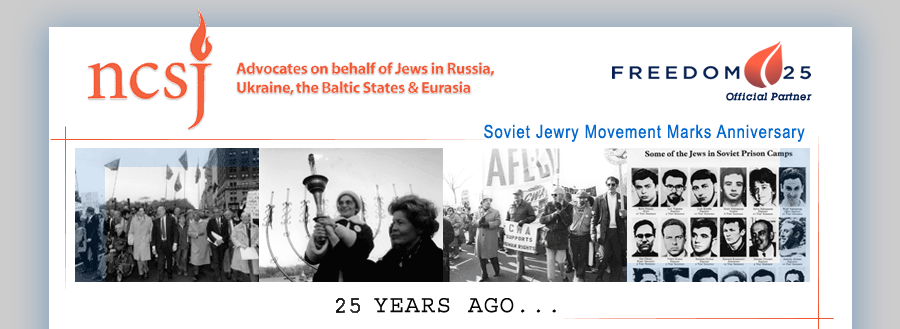

When we learned that Mikhail Gorbachev was to meet with President Reagan in Washington, the National Conference on Soviet Jewry organized a “Mobilization for Soviet Jewry”.

On December 6, 1987, we came from all across the country to show our support. In an incredible show of solidarity, more than a quarter of a million people – Americans of all faiths and backgrounds – filled the mall in front of the U.S. Capitol to demonstrate on behalf of Soviet Jews.

As Jacqueline Levine, National Chair of the Mobilization said, “It was the culmination of the struggle for emigration of Soviet Jewry, which is, next to Zionism, the 20th century’s most successful Jewish

movement.”

Shortly thereafter, the USSR collapsed and one and a half million Soviet Jews emerged into freedom!

To celebrate that galvanic movement in modern Jewish history and our role in helping to achieve it, the National Conference on Soviet Jewry is hosting a reception at the Capitol honoring Congressional leaders who were instrumental in the struggle for Soviet Jews.

NCSJ will also conduct a symposium to explore the lessons we can learn. Entitled “From Oppression and Isolation to Freedom and Rebirth: The Past, Present and Future of the Soviet Jewry Movement.” The goal: a formal assessment of the movement’s successes and limitations that will help the Jewish community face new challenges when they arise.

Some lessons are clear already. One is that passivity cannot be tolerated, that doing nothing is unacceptable. Our parents’ and grandparents’ generations were able to do little in the face of the Holocaust. People could not comprehend the extent of the horror being planned and perpetrated and relied on the tactic of the powerless: lying low, keeping quiet, being

shah-stil-niks. Moreover, and more importantly, they had little political leverage.

But we have no excuse to be silent, and our voices have considerable political weight.

We have learned that individuals can save lives. In the mid-1980s, a couple, early activists in the Soviet Jewry movement, traveled to the Soviet Union to visit

refuseniks and boost their morale. They knocked on the door of the apartment of a refusenik whose name and address had been given to them by the NCSJ. They had been told that the man was depressed and that it was important to make contact. There was no answer, so they knocked again. Again, no answer but they thought they heard a noise in the apartment so they continued to knock. Finally, the door was opened a crack. “We’re here from the United States to visit you,” they said into the silence. “How do you know who I am?” the man asked in halting English. “Everybody in America knows who you are. You are a hero!” The door opened and the couple entered the apartment. They saw a rope hanging from the ceiling. The refusenik they had come to visit, having lost all hope for his future, was in the process of committing suicide when they arrived at his door. Their visit literally saved his life.

But individuals can only do so much. The couple who happened upon the desperate refusenik would not have known whom to visit without the organizational work of the Soviet Jewry movement. Each of us who stood up for Soviet Jewry would have been a voice in the wilderness without the collective action of the entire Jewish community.

That day in Washington, 20 years ago, we stood up for justice and righteousness. We stood up for freedom and for the privilege of helping to make miracles happen in our own time.

SERMON #2

Sermon by Rabbi David Hill

Queens, New York

This Chanukah will make two very important anniversaries in Jewish history: the 40th anniversary of the struggle for freedom of the Soviet Jewry and the 20th anniversary of one of the largest marches on Washington at the time.

Encouraged by the victory of Israel during the Six Day War in 1967, Jews living in the Soviet Union began to rebel and demand freedom. The

refuseniks, as they were known, would practice their Judaism in secret at great peril. Many were arrested, harassed by KGB or even sent to Siberia. But their plight did not fall on deaf ears.

The National Conference on Soviet Jewry made this a human rights issue. We organized trips for Americans to visit their Soviet brothers and sisters. We created bracelets that bore the names of

“Prisoners of Conscience” to be worn until that person was free. We raised American Jewish consciousness about this issue, having learned difficult and valuable lessons about silence after the Holocaust.

On December 6, 1987, 250,000 people marched on Washington to free the Soviet Jewry. The rally organized by the NCSJ saw Jews come from all across the country on the eve of Soviet Premier Gorbachev’s first U.S. visit to demand: “Let my people go!” It was this unprecedented display of unity by the Jewish community worldwide that led to the gates being opened and Soviet Jews being allowed to emigrate and be free of religious persecution.

I still vividly remember when I was chairman of a dinner for the Jewish National Fund. With one thousand people present, every table had Chanukah menorahs dedicated to the

refuseniks and the Prisoners of Zion in Russia. And one thousand people lit a candle on their behalf and all our brothers and sisters in then-Russia.

Twenty-five years have passed since that historic moment. Approximately 1.5 million Jews remain in the former Soviet Union. Thanks to the efforts of the American Jewish community and NCSJ those Jews are free, but they still need our help.

The work of the National Conference on Soviet Jewry has continued up to the present day. Our organization is dedicated to the safety of every Jews in the FSU. They are allowed to freely practice their religion, but it is not without dangers. Anti-Semitism and hate crimes run rampant, but NCSJ is still there to help. For example, as recently as about two weeks ago when 15 young

Lubavitch students were arrested in the Russian city of Rostov, it was our Executive Director, Mark Levin, who through his expertise and contacts with American diplomats was instrumental in freeing the young Jews from prison and enabling them to fly to Israel.

The 1987 rally marked a significant moment in history. The world saw how much could be learned from the Jewish community. It also created a true sense of Jewish peoplehood that spanned countries and continents, and that bond still exists today.

We are still our brother’s keeper. And it is the National Conference on Soviet Jewry, whose only mandate is to secure safety, both physical and spiritual, of still more than one million Jews living there who keep our brothers and sisters safe.

SERMON #3

The Miracles and the Challenges for the Jewish People

Sermon by Rabbi Nina Beth Cardin

Baltimore, Maryland

Every generation has its challenges. Every generation is tested. We are known and remembered for how well we respond. For the past four decades, in regard to Soviet Jewry, we have passed the test. In December 1987, we gathered 250,000 strong to march on a bitter cold day in Washington, to give voice to a call that President Gorbachev could not ignore: Let Our People Go. Soon thereafter, the floodgates opened. What started as a movement on the margins, embraced by students, became a defining moment in American Jewish history. Today, we have our souvenirs: POC – Prisoner of Conscience – bracelets (engraved with the names of

refuseniks, which we wore in solidarity with them), our red scarves (double-knit, which were distributed at the march to help us fend off the cold), and the present company of millions of Jews from the former Soviet Union

(FSU) in our towns, our communities, our homeland, and even our families.

Chanukah is the time to celebrate miracles. Like the Jews in the days of the Maccabees, the Jews in the FSU also were prohibited from studying Torah, or in the words of the prayer we say on this holiday,

l’hashkiham toratekha; and they were denied the right to practice their traditions,

l’ha’aviram mhukei retzonekha. And miraculously, a small band of Jews, bringing America to our side, stood against the mighty power of the Soviet Union - and the Soviet Union blinked.

That was one grand miracle. And now it is up to us to perform the daily miracles of helping the elderly in the FSU, of giving the young the Jewish learning and passion their parents never could, of embracing the Jews from the FSU in our communities in American and Israel. That miracle is not like the miracle of victory; not achieved in a moment, once and done with. The daily miracles still beckoning to us are performed the way we light our Hanukkah candles, reaching out to touch the other, one by one by one.

We, and the miracles, are not done. Over a million Jews still reside in the FSU amid difficult financial conditions and increasing demonstrations of anti-Semitism.

Even while they make great strides in building Jewish cultural and community centers, even as they work to re-establish institutions of learning, even as campus Hillels instill pride, programming and energy among Jewish college students, much more needs to be done.

Many Jews will not leave the FSU. That is their home. And we cannot forget them. In this act of remembrance and connection we are inspired by the words that Jacob, now named Israel, spoke to his son, Joseph (Genesis 37:14): “Go, see how your brothers are faring, and how their herds are doing. And then bring word back to me.”

Our brethren remain there, but they and we are all children of Israel. It is incumbent upon us to continue to see how they are doing; and how their possessions are holding out. And then we must bring back word, to our synagogues, our communities, our Federations and to the public officials, both here and in the FSU, to assure that our brethren do not suffer. This Chanukah, while we reflect on those challenges we have conquered let us not forget those that lay ahead. May your Chanukah celebration be full of joy and miracles.

SERMON #4

Sermon by Rabbi Jack Moline

Alexandria, Virginia

We can choose to debate all we like about the historical facts of the story of

Chanukah. What we know for certain is that generations later, the architects of our tradition found inspiration in the brash courage of a small band of devoted Jews. Rather than give into oppression, goes the story, they stood up to the superpower of the day and kindled a light that burned not just for eight days, but for the ages.

This week marks the twentieth anniversary of the historic Freedom Sunday rally when 250,000 Americans marched on the National Mall on behalf of Soviet Jewry crying: “Let my people go!” It was a crowning achievement for groups like NCSJ:

Advocates on behalf of Jews in Russia, Ukraine the Baltic States & Eurasia, who led the way in our community, creating

“Prisoner of Conscience” bracelets, organizing trips for Americans to visit refuseniks, and lifting the cause high on the national agenda. And that’s reason enough for me to think back.

When I was a pisher, a college student in Chicago in 1972, I took a group of high school students wearing tee-shirts that said “Save Soviet Jews” to an exhibit of Soviet art that was one of the first to tour the United States during the Cold War. The resulting brouhaha landed me as a plaintiff in federal court, where I in my ponytail sued the Field Museum for my constitutional right to assemble with others, in front of Judge Julius Hoffman, who had just concluded the trial of Abby Hoffman, Jerry Rubin and the other members of the Chicago 7.

We won, but that fact is not important except that it got me ushered into a back office of the museum the next time I was there by two guys in dark suits and earphones. They wanted to know what it would take to get me to call off the visits. And I named a name – a particular high-profile refusenik. They picked up a phone and called the State Department, or maybe they pretended to. And they told me they’d get back to me – and asked me if I would stop the visits as a sign of good will. I would not. I did not. And while Gavriel Shapiro eventually emigrated to the West, and while I have no idea whether it was because a twenty-year-old with all the

chutzpah of a twenty-year-old demanded it, I realized that I and others like me could do more about the things we cared about than just complain.

We, with the brash courage of devoted Jews, stood up to the superpower of the day and kindled a light in the hearts of our peers, our children and our seniors. That passion has continued to burn for two generations, animating social activism on behalf of Israel, human rights, religious freedom and Jewish identity – all rays of light given off by that flame.

Those of us who have lived our lives in the interim can look back and see what we accomplished. Never mind the organizational impact the activists in the Soviet Jewry movement have had. We can look back and see the lives that were changed.

In 2007, the twentieth anniversary of the March, I used a tool unavailable to me in my activist days. Wondering whatever happened to the man who inspired my courage, I

"Googled" his name. There he was, teaching Russian literature at Cornell. We had a quick exchange of emails. I thanked God for his quiet life of twenty years. He thanked me for helping to make it happen.

It is a story you tell your children as you light the Chanukiyah after twenty-five years, and your grandchildren after fifty.